(a talk I gave at Creating Connections 20025, UCLA)

In the last month or so, I’ve begun to understand writing as a practice of freedom.

And I’ve come to see that those of us who value freedom, should promote writing.

Timothy Snyder’s book On Freedom offers five key ingredients for freedom.

These include sovereignty, unpredictability, and factuality. (The other two are mobility and solidarity.)

Sovereignty is the development of a “sense of what ought to be and how to get there.” It’s the opposite of resignation and learned helplessness.

Unpredictability is necessary for freedom since predictable people are much easier to control.

Snyder says that unpredictability arises from our need to prioritize our multiple values differently in different situations. I value academic rigor and kindness. Sometimes I need to prioritize challenging my students to meet a deadline; sometimes I need to prioritize being understanding about their missing one. The circumstances affect my decisions.

If we only have one value that outranks all others, every time, then we are predictable.

This unpredictability is also needed in a working democracy. We have to compromise with other community members, choosing which values we can temporarily put aside in the service of promoting others that we might share.

And a third necessity for freedom is factuality. We have to be able to tell what’s true and what’s not.

Reading Snyder brought me back to my early research, in which I studied Gertrude Stein’s observations of human behavior in Occupied France. She welcomed the American soldiers after the war, but she worried that they were too much like the Germans. Some convergent evolution had made it so the always-hustling Americans didn’t have time to think for themselves and were becoming what she called “yes-and-no job men.”

As we have “yes [people]” in government and business, we are getting “yes [students]” in the classroom. They are not giving themselves the time to think and learn. Perhaps efficiency has become the shared, common, and single overriding value in the USA.

We might like to imagine that students are having long and thoughtful conversations with intelligent ChatBots, but as they enter prompts into AI-LLMs, it’s becoming easier and easier for students to just say “yes.” Cut, paste, voila. And if these students are thinking at all about the words that are generated, they are thinking in predictable and prefabricated phrases.

It’s been shown that people who use AI regularly provide less and less oversight to it; they assume it’s working, it’s fine, and just “yes.” Yes, we are supposed to be paying attention, but that gets boring when we aren’t actually thinking or doing anything.

As one of my CS students has argued article: we cannot assume that checking the quality of text is easier than producing quality text in the first place.

Probably most of us have seen students turn in AI-generated work that they did not check at all.

With the sudden release of AI LLMs, and their quick adoption in so many facets of life, we must imagine a moment in history when most writing is done by AI-LLMs.

What is gained? And what is lost?

In spite of their own spoken fears (existential crisis, don’t release AI until we get in our bunkers, etc.), the company’s owners mainly tell us about what might be gained. So let me focus on the losses.

Let me just start by looking at what the writers themselves lose. When I think of what’s lost, I see that writing is an opportunity, not a chore. Writing helps us TO DO important things. NOT writing KEEPS us from those important tasks.

This aligns with Snyder. He emphasizes the importance of “freedom to” do stuff, and he points to the problem of just valuing “freedom from” restraint. AI may free students FROM the work of writing an essay for a class, but by skipping that opportunity, students are not learning the skills that will give them the ability and freedom TO DO the things they want to do in life.

NOT writing, for example, lets AI produce for us the “pre-fabricated phrases” that George Orwell laments in “Politics in the English Language.” Notice the phrases that Orwell uses to describe language that prevents us from thinking: pre-written, empty, dishonest, intimidating.

(I hate to think how some of the smartest students in the world, our UCLA students, are so intimidated by AI that they trust it more than they trust their own abilities.)

By writing, we are insisting on our own sovereignty, our own self-determination, our own individuality, priorities, values, and decisions. When we realize this, we realize that writing is a practice of freedom.

In Snyder’s words, “Freedom is about knowing what we value and bringing it to life.”

More directly pertinent to writing, Snyder also writes,

“Freedom is positive; getting words around it, like living it, is an act of creation” (xix).

So, choosing the words with which we express our experiences and observations is freedom. Gertrude Stein liked to play round with the opening words of the Star-Spangled Banner, “Oh say can you see?” She revises this to “say what you see” and even “announce what you see” (Geographical History of America, 162-3, my italics).

We must be vigilant and not let others see for us. “Like living it,” freedom is also “getting [our own] words around it.” It “is an act of creation.” (Snyder, xix).

And we have to give our science students practice with saying what they see and getting their own words around it, or they will all end up working as product defense firms, rationalizing preferred results instead of doing open and good-faith science.

So let’s frame science as a practice of writing.

In his recent “Open Letter to Graduate Students and other Procrastinators,” Dennis Hazelett asserts that “it’s time to write.” He begins, “Let me begin with a hard truth. As scientists, writing is our chief activity. It can be argued that it is the only thing we do that matters.”

He does not back down later in the article. Instead, he writes, “If you are in the sciences, at the PhD level, writing is the only thing you do that matters. The most important trait for you to have to have lasting impact on humanity, and indeed to sustain your career, is your ability to have ideas, to gather evidence in support of them, and to publish them. Your job is to have ideas and spread them so that they impact other people’s work. Writing is your job. Nothing else. Therefore, everything else that you do is subservient to the activity of writing. Let this revolution take place in your mind.”

So let’s do that.

If “everything else that [a scientist does] is subservient to the activity of writing,” what changes? I think this means that you take way better notes in the lab. You do a much better job of marshalling your citations and keeping track of them with a citation manager. It means that you are very careful to develop an argument, one you can express, for why you are making each decision in the methods section. It means that you have good reasons for taking scientific research this direction instead of that one.

If a beaker bubbles up in a forest and nobody writes about it, did the beaker’s contents bubble up? Or rather, did its doing so aid human understanding in any way?

Writing is the ultimate goal of science because through writing, we advance human understanding, both for ourselves and others.

Hazelett also writes, “The only kind of thinking that matters in science is structured thinking. The only way to give structure and substance to your thoughts is to write them down. Writing. Is. Thinking.”

(Let me just add that there are a lot of articles on this topic, including ones by a writer and editor, a historian, two psychologists, and a chemist.)

Hazelett describes the power of writing: “There is something magical that happens as words travel from your frontal cortex through the motor centers and get translated into complete sentences and paragraphs. They get seen by the other parts of your brain. They can’t hide away from the scrutiny of the grammar police in the protected little hovels of your hippocampus. No longer can they fester in your language center, gossiping with each other about how sublime they are. Even whole sentences wilt in the sunlight when considered in a procession of other sentences, or when asked to justify themselves before the withering gaze of the section title.”

To repeat that, writing makes us honest with ourselves and logical about the information and ideas. We have to think about the words and ideas as we produce them. We have to let them speak back to us and tell us what we are saying, what makes sense, and what doesn’t.

This honesty, factuality, and logic are related to freedom. As Snyder writes, “Observing for oneself and thinking for oneself are both necessary for self-determination and freedom.”

Snyder’s a historian, but “Observing for oneself and thinking for oneself are both necessary” for science, too.

The 2025 Proceedings of the National Academy of Science recently published several responses to the question, “How should the advancement of large language models affect the practice of science?”

Bender, Bergstrom, and West point to MANY reasons that humans need to write about their own scientific research, write their own literature reviews, and just write.

Here are seven of them.

The first is obvious: writing allows us the opportunity to formulate, organize and refine our ideas.

But second, humans doing the writing and thinking contributes to what they call “epistemic diversity.” In other words, instead of a consolidated large language model writing from a collected and concentrated set of knowledge, humans are widely distributed–geographically, epistemically, culturally, in terms of our values and priorities, and educationally. In other words, humans are likely to know and care about different stuff, and this diversifies our approaches to problems and improves science.

Third, science requires transparency. We may not be able to be as objective as we once thought we could be, but we can try to be transparent. Humans can do that, but an LLM cannot. They are black boxes: stuff goes in, and stuff comes out, but we don’t know exactly why or how. That mysterious processing has no place in logical science.

Fourth and Fifth, the point of science is an increase in human understanding of the world around us. Students need to write to understand what they observe in a lab experiment. Human scientists must do their own literature reviews so that their observations, values, and priorities can notice what gaps in knowledge exist and matter. These preferences lead to our directing future work in science. In other words: the fourth reason is that writing supports human understanding, and the fifth reason is that humans must maintain their own control over the future directions of science research.

Sixth, the real work of thinking is synthesis. Humans add value to scientific findings by synthesizing ideas and observations together into bigger pictures. We do this through writing.

The seventh point is a reiteration of their title: “Science is a social process that cannot be auto-completed.”

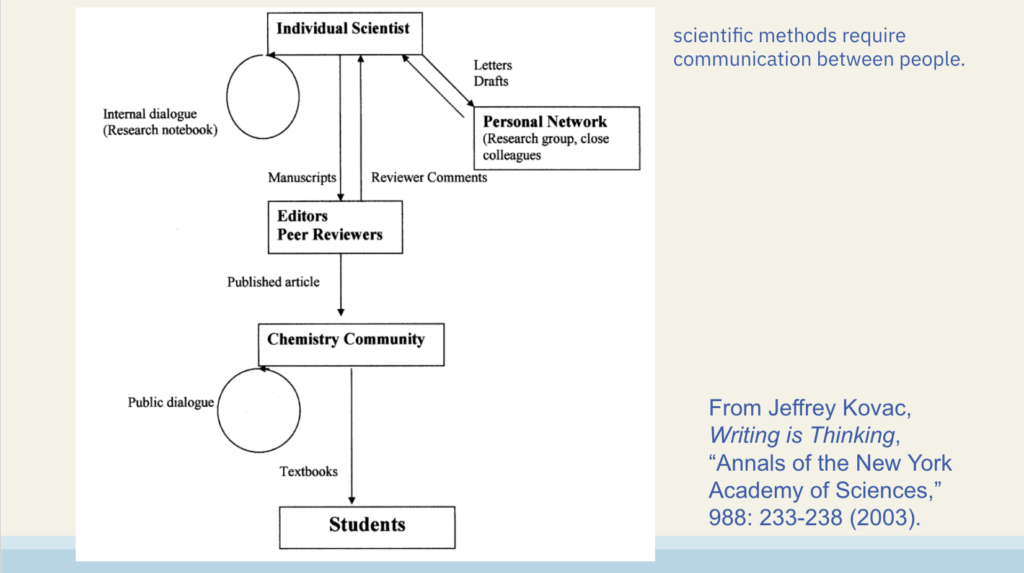

As Kovac charts out with a Feynman diagram, scientists are in constant communication with their networks through letters and emails and drafts.

They have an internal dialogue with themselves using a lab notebook. They send manuscripts to editors and peer reviewers, and they get comments back. They communicate with the whole community in their field via their published articles. Other scientists communicate these findings through textbooks and lectures and slides to students, and to the general public and to policy makers, who then participate in dialogue about it.

All this communication must take place for science to get done and to increase human understanding and to influence our world for the better. It all involves humans writing for their own benefit and to communicate with others. What’s lost if we do not do this writing? What’s lost if AI LLMs intervene and mediate in all these steps? I invite you to consider those questions.

Over the course of this talk, I’ve tried to develop your intuition about the deep and necessary role of writing in science, learning, human understanding, and self-direction.

If we frame writing as freedom, as sovereignty, as a kind of self-determination both individually and for human understanding and the progress of science, then writing becomes the main task of science. Hazelett emphasizes individual career success, but it’s time to highlight writing as the whole key to the important endeavor of doing science. Once that’s clear to teacher and student, then the writing assignments flow naturally.

So let this revolution take place in your mind. If writing is the main job of scientists, how does that change the role of writing in your STEM classes? How does it change your attitude toward writing, and your practices of writing, in your own research?

I have two examples below of possible assignments, and my fellow panelists will offer several others (these are available at the conference site), but I hope you’ll jot down what types of writing assignments occur to you and share them during our discussion period.

Two examples:

#1: Developing honesty and empathy

Think of a project you’re working on. There must be a reason you are doing it: a gap in the existing knowledge, and some motivation to fill it (possibly b/c doing so would be for the public good). Someone disagrees with you. Or someone else is wrong. Or a previous researcher has made some progress that direction, but now you want to take a turn and continue a different direction. Whatever it is, and however strongly, you probably disagree with somebody about your work, or about their work, or about the state of the field, or about the promise of one line of research or another.

Try to articulate that disagreement as clearly as you can in writing. Explore it enough that you can pinpoint the exact extent of your alignment and disagreement. I hope you’ll be able to feel your way around the problem, starting with empathy and respect, and (ideally) ending there (since that researcher was probably doing their best, too). But if your honest clarity of expression and thought leads you away from thinking that you share values, try to articulate why. What is the difference in values? Or what is wrong with (or inadequate about) the methods or data or conclusions of that other research?

#2 Considering and promoting one’s values

First, establish some principles. You can pick your own, but here are some possible ones to consider (from Medvecky and Leach):

Communism: Science is for the benefit of everyone

Universalism: Science from everywhere and everyone is worthwhile

Disinterestedness: Science should not be skewed by money and power

Skepticism: Uncertainty and methodology must be communicated

Educational: Science findings should be communicated in ways that also teach how science is done

Interactive and democratic: Scientists should be in conversation with others, not shutting down conversations

What else might we add?

Choose one short science article and evaluate how the author(s) achieve (or don’t) the principles you value most about good science writing.

You might have an article in mind, or one you can call up, but I’ll hand out a short one if you do not. “The Satellite that will “weigh’ the world’s 1.5 trillion trees” (Esme Stallard, BBC, 29 April 2025)

References:

Bender, Emily M. Carl T. Bergstrom, and Jevin D. West. “How should the advancement of large language models affect the practice of science?: Science is a Social Process that Cannot be Autocompleted,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (Vol 22, No. 5), 2025.

Harel-Canada. Fabrice. “Sandcastles in the Storm: Revisiting the (Im)possibility of Strong Watermarking.” Submitted to ACL (Association for Computational Linguistics) 2025. Preprint at arXiv.

Hazelett, Dennis. “An Open Letter to Graduate Students and Other Procrastinators: It’s Time to Write.” Nature Biotechnology. Volume 43, March 2025.

Jeffrey Kovac, “Writing is Thinking”, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 988: 233-238 (2003).

Hao-Ping (Hank) Lee, Advait Sarkar, Lev Tankelevitch, Ian Drosos, Sean Rintel, Richard Banks, and Nicholas Wilson. 2025. “The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers.” In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘25), April 26-May 1, 2025, Yokohama, Japan. ACM, New York.

McLuhan, Marshall. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1962.

Medvecky, Fabien and Joan Leach, An Ethics of Science Communication. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave, 2019.

Mintz, Stephen (historian). “Writing is Thinking.” Inside Higher Ed. 2 November 2021.

Oatley, Keith and Maja Djikic. “Writing as Thinking.” Review of General Psychology. (Vol 12, No. 1) 2008, 9-27.

Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language.” First published: London: Horizon, April 1946.

Parker, Ian. “Absolute Powerpoint, New Yorker, 20 May 2001.

Snyder, Timothy. On Freedom. New York: Crown, 2024.

Stein, Gertrude. The Geographical History of America, or The Relation of Human Nature to the Human Mind. 1936. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1995.

Warner, John (writer and editor). “Writing is Thinking.” The Biblioracle Recommends. Substack. 24 Sept 2023.