Jonathan Bunton

May 14, 2020

Abstract

Empathy is a core character trait that is often forgotten in the realm of STEM students. It is a deeply humanizing characteristic that allows us to understand and connect to other people, like an emotional ethernet cable. In this work, I discuss some figurative “empathy bicep curls” that I used to develop empathetic habits. In particular, I explored connecting to fellow lab-mates in a strictly non-lab setting, through casual check-ins and weekly video calls. During these weekly calls, I tried to read people’s moods, like a mystic crystal ball reading of green-boxed video streams. I used this mood-reading to engage everyone, sowing the seeds of a deep support system in both my lab group and my larger network of friends.

Introduction

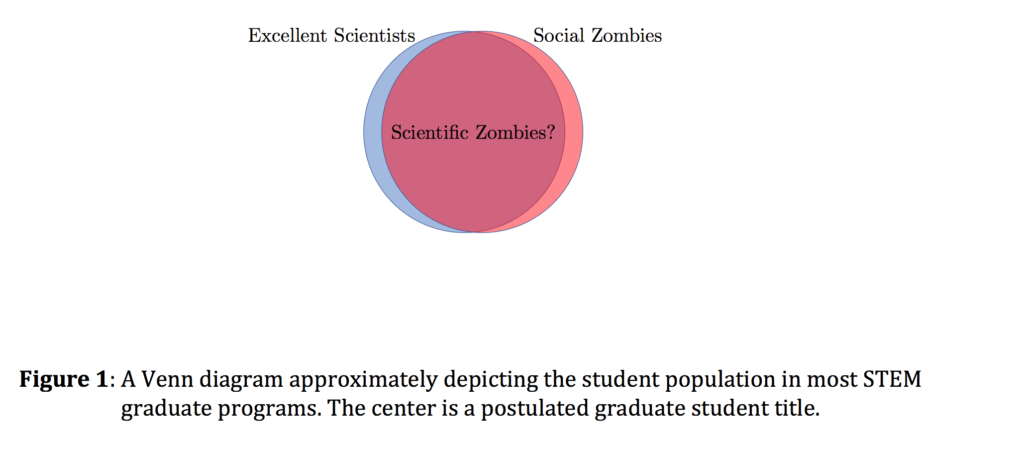

Graduate school in STEM is excellent at producing two types of people: excellent scientists, and social zombies. Moreover, if we were to draw a Venn diagram of social zombies and excellent scientists in a STEM graduate program, we might guess the result would look like nearly a solid circle (see Fig. 1).

This result is of little real blame on anyone involved–graduate school inherently requires an immense amount of research and work, which quickly eats away time. And graduate students are generally happy to do this work, with little regard for their mental health. If this statement seems doubtful, a quick cursory glance through some of the top posts on various forums reassures that working until burnout is a common feeling.

A major part of this problem arises because graduate students stop treating themselves and their lab mates as real people. This isn’t to say that lab meetings suddenly become awkward menageries of mythical creatures, but more that students forget how to interact with each other on a simpler, person-to-person level.

The goal of this experiment was to remind myself and my lab of the importance of these sorts of interactions. I often use this “Everyone Poops!” style of reminder to keep myself humble, and also to muster the courage to talk to people. It’s the same method I used when I asked my girlfriend to date me while standing in a unitard at the National Mall. (The deeper reasoning for this picture is an excellent story that I’d be happy to explain another time.)

The “empathy workout” that I felt aligned with the importance of humanizing people, and in particular graduate students, was item 12 on the assignment list for the empaty experiment:

Make at least one personal contact with one of your fellow students (or lab-mates or coworkers) each week. It can just be “hi, how are you doing?” or you can share a personal story, one that you think the other person can relate to and that may then help them connect to you better afterward (Alan Alda, If I Understood You, Would I Have this Look on My Face?, 146-7).

Using this suggestion as a guideline, I doubled down on these efforts: I organized a weekly lab video call that did not include our professor, and I reached out weekly to a student in my lab who is quarantining alone.

My lab is fairly social, especially when compared to others in our area. Before the quarantine came into effect, we often had small social gatherings that were unrelated to the lab itself. We played games, went for drinks, even played instruments together.

During our time apart, however, I felt we needed something to remind us that we are more than just “work associates,” we’re friends. And moreover, that we are all here to lean on in these odd times. More than anything, I argued to myself, this process would humanize us, and remind us that we are all just people coping as best we can. This “humanization” of myself and my lab mates is arguably the ultimate goal of empathy: to understand and relate to each other, despite cultural, social, and computer screen divides.

Methods

In the current state of quarantine, video calls are the new norm. They pranced into everyone’s homes as though they had been there all along, silently creeping into our offices, our kitchen tables, and even our closets. It’s a sad state of affairs, but it is the world we live in. It is about as close as we can get these days without breaking Center for Disease Control guidelines.

Knowing this situation, I organized a two-pronged approach to this empathy exercise:

1. Reach out to one lab member a week who I know is quarantining alone.

2. Organize a group video call, outside of normal lab meetings, to keep everyone connected.

There are several international students in my lab, which means there are several friends of mine who are stuck alone in studio apartments, away from their families, during the quarantine. I sent them messages weekly–some were more conversational than others–and tried to gauge how comfortable they felt talking to me. The goal with this experiment was to not only provide a support system for these students (and myself), but to try and understand the immense difference in quarantine scenarios between us.

With video calls, I sought to keep our lab community close through quarantine. We needed a space where we were allowed to be just people, not research machines. To further this goal, I included several members of our extended friend group, to keep the call from feeling too much like a repeat of each week’s multi-hour lab progress report. I tried hard to note how everyone felt and seemed to be handling things both when talking, but also when just sitting on camera. Did they seem distracted, nervous, bored? Aside from the goals of better camaraderie, I wanted to learn to read audiences in video calls, because this skill seems to be invaluable these days.

Results and Discussion

I followed this exercise for approximately four weeks. This meant four weeks of reaching out to a person alone, and organizing a non-work video call.

Over the course of just sending messages, I learned more about my lab-mates who were living in isolation. Not just what they were working on, but what they did in their free time, and what they thought about while relaxing at home. This slightly deeper connection helped me understand them, and I’d argue to be a better friend.

I learned that one of my lab mates has become a plant parent several times over, by snagging and re-planting pieces of several neglected plants around his apartment complex. In an entirely opposite direction, he had become immensely invested in a series of war documentaries. By proxy, I learned a lot about the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War from an Argentinian engineering graduate student.

I also learned all flights to Argentina were cancelled, and he had nowhere else to go. He said his plants helped keep him sane, and he had a strict regimen of “class times” to divide his workday. His admission of this was sobering, coming from a person who is typically the happy-go-lucky type.

Meanwhile, I learned that another lab mate was extremely okay with being alone, because he was a less social person to begin with. I learned he had dug up some archaic and unused programming languages and trying to re-learn them. Some people are born masochists, I suppose.

Though not necessarily massive leaps, these conversations were enlightening. I spend so much time connected to these people, since my lab is basically a second home. But small conversations like this–especially during such uncertain times–help build us together into a support system.

The video calls, by contrast, started slow. Nearly everyone in my lab had used Zoom for our cross-campus research meetings in the past, so we all felt some odd pressure to stay professional. This pressure manifested itself with awkward fits of “So how is research going?” and “What’ve you been working on?” when conversation lulled.

I did my best to break these habits by instating a no “shop talk” rule during these calls. These calls were meant to be our lab utopia–a free space for us to be normal people, not just runners on the graduate research hamster wheel. To further limit “shop talk,” I invited some friends from outside the lab to join. These people helped set a distinctly different tone than in our typical weekly lab meetings.

The calls eventually became something expected—friends would text to remind me to send out invites to the week’s call. If anyone missed, they would later check in with me to see if everyone was okay, and also how the call went. It became a weekly pulse check on everyone in the lab: are they here? If not, has anyone heard from them? Especially in this time of quarantine, these weekly calls seemed to be a moment for us to take stock of the lab as people, building a tighter network of people to depend on.

I also tried to identify the mood and level of engagement of different people in the calls, especially when not talking. This meant learning a whole new set of social cues, watching people in a small green box as they scroll through their phone, or nod absentmindedly against a shimmering and pixellated “The Office” backdrop. The audience-centered empathy skills for in-person speaking are familiar and easy to read after much practice, but translating them to Zoom calls feels like trying to infer typical lion behavior from my dad’s house cat “Simba.”

I used these mood gauges to try and engage everyone as best I could, teasing people into un-muting microphones and turning on video streams. “We’re good enough friends to hear each other’s static,” I reassured everyone.

As the weeks went on, I found it easier to identify people who needed to be involved. This process felt like re-learning elementary lunchroom etiquette, remembering to invite the sad-looking boy sitting alone to come eat with everyone else. However, unlike the sad-looking boy in elementary school, people in Zoom calls are usually quite content to sit looking at their cell phone instead of talking to a computer screen of ten floating heads.

Learning these mood cues through video call reminded me a lot of the initial test we took, reading emotions through just eye expressions. I think in future weeks, I could further my video calling exercise by trying to assign these sorts of emotion labels on my lab mates while in the call. Ultimately, I may continue this experiment with several small variations, with my friends as the unknowing test mice in my empathy laboratory.

Conclusion

Empathy is an immensely useful characteristic of effective communicators, researchers, and friends. It is an incredible humanizing tool that allows us to connect with an audience, a reader, or a group of friends. I took this experiment as an opportunity to humanize my lab environment, by initializing weekly video calls to keep touch during the quarantine.

Though video calls are common these days, my lab only ever participated in one all together on a regular basis: research meetings. While important, these meetings are a rapid- fire pop-quiz on the science we worked on the past week, with few pauses to connect as people. I felt my lab could retain and strengthen its own empathy support system by having a special time set aside where we were allowed to be people, and talk to each other as people.

These weekly calls started as awkward chats, but eventually became an anticipated occurrence. It’s easy to forget through all of the research meetings and classes that under it all, our lab is also a group of good friends. I hoped and felt that these calls reminded us of that fact, while strengthening our empathy networks.

My own empathy skills could use continued work, and I plan on using these weekly calls as a training ground for reading audiences over video call. As we brace ourselves for an online fall quarter like the Starks preparing for winter, these sorts of skills seem more invaluable than ever.

Even more so, I need to retain the ability to connect to other people, lest I emerge from quarantine a full Neanderthal, unsure of how to appease the lab group tribe.