A longer version of an article published in Adbusters, October 2021, which was an adaption/excerpt from an article published in ISLE in 2016.

A longer version of an article published in Adbusters, October 2021, which was an adaption/excerpt from an article published in ISLE in 2016.

A research paper by Jacy Black

Abstract

Empathy is understood as an affective and cognitive human skill that incorporates understanding the feelings of others and a personal emotional reactions to those feelings. The positive relationship between empathy and self-reflection has been explored in scientific literature but the nature of this relationship remains ambiguous. With the understanding that empathy is a beneficial skill that can be improved, this work serves to explore self-reflection in journaling as a method of improving empathy. The experiment was conducted as a between-subjects design where participants were randomly assigned to emotional-awareness journaling or daily activity journaling conditions. The Empathy Quotient (EQ) for Adults and the Social Stories Questionnaire (SSQ) for Adults were utilized to measure the participants’ empathy levels before and after the experimental manipulation. It was hypothesized that participants in the emotional-awareness journaling condition would demonstrate significant empathy score increase across both tests and that the daily activity journaling condition would show no significant score change on these measures. In the emotional-awareness condition, most participants showed an increase in EQ and SSQ scores while SSQ scores stayed fairly consistent among participants in the daily activity journaling condition. The results of this study suggest emotional-awareness journaling can be a beneficial activity to promoting empathy.

Introduction

Psychological mindedness (PM) is understood as an awareness and comprehension of mental processes such as thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, of which empathy and self-reflection are essential parts (Beitel, Ferrer, & Cecero, 2005, pp. 740-747). One aspect of empathy, and therefore psychological mindedness, is perspective-taking, or the “transposing of oneself into the thinking, feeling, and acting of another,” (Dymond, 1950, p. 343). A literature review conducted by Gerace, Day, Casey, & Mohr (2017) evaluated the relationship between self-reflection and perspective-taking according to previous research. Gerace et al. (2017) advocate the importance of accurate self-knowledge in self-reflection, thus impacting the empathetic skill of perspective-taking (pp. 4-24). This is further supported by experimental study results that demonstrate a positive relationship between personal insight and empathy (Dymond, 1950). However, despite supporting the relationship between self-reflection and empathy, Gerace et al. (2017) recognize the ambiguity in studies exploring this relationship and the need for further research into these two skills.

As self-reflection impacts perspective-taking, it stands to reason that activities designed to improve self-reflection and accurate self-knowledge can foster the development of empathy. Likewise, as empathy is widely recognized as a beneficial skill, exploring potential methods of improving empathy is a worthwhile endeavor. Journaling is one such method that can promote the development of empathy. It is our personal understanding that journaling can be an important introspective practice to improve emotional awareness and self-knowledge when utilized for this purpose. It was through this personal interest and experience that we began our study. Additionally, under the presumption that journaling proves to be effective in promoting empathy, this is a relatively inexpensive activity that can be easily and widely implemented.

Previous research suggests the practice of journaling may be beneficial in improving empathy, however journaling was not the main subject of previous studies and not all results were empirically based. Doctoral research conducted by Patton (2019) explored journaling, among other methods, to promote learning and empathy within the classroom. The results of her thesis concluded that journaling fostered empathy with regards to perspective-taking but not other explored measures, attributing the results to students’ ability to utilize journaling to process their own emotions while learning about the emotions of others (Patton, 2017, pp. 117-118). Another experiment explored journaling as a method to encourage self-reflection and awareness in students from a client-centered Occupational Therapy program (Jamieson et al., 2006). While it was assumed that journaling was beneficial, the assessment lacked an empirical evaluation. This prevented any determination of whether journaling significantly impacted the training experience and student empathy (Jamieson et al., 2006, pp. 79-82). Research focused solely on the practice of journaling, and how it should be utilized, is required to measure its impact on empathy more directly.

This study explores the relationship of journaling on empathy. We anticipate that the impact of journaling on empathy scores will be mediated by the way in which journaling is utilized. It is hypothesized that an increase in empathy scores, determined by the Emotion Quotient (EQ) for Adults and the Social Stories Questionnaire (SSQ) for Adults, will be significant when journaling content is centered around emotional-awareness, as opposed to no significant change in empathy scores when journaling consists of reiterating daily activities. This hypothesis is based upon the principle that reflection upon one’s emotions is important in fostering empathy.

Method

The experiment was conducted as a between-subjects design focused on the effects of journaling utilization on empathy scores. Undergraduate participants were randomly assigned to one of two journaling utilization conditions, tested on scores of empathy, and engaged in journaling for the duration of one week. Afterwards, they were again tested on empathy and the pretest and posttest scores were compared for significance.

Participants. Eight undergraduate students were recruited from the University of California, Los Angeles for a week long study (M=3 , F=5, Mage= 20.43, age range: 19-22). All participants are undergraduate colleagues of the researchers. One participant’s data was excluded from data analysis as they requested to leave the study. Refer to Table I for participant information according to group.

| n | Mean age | |

| Group 1 (Control) | 4 | 20.67 |

| Group 2 (Experimental) | 3 | 20.25 |

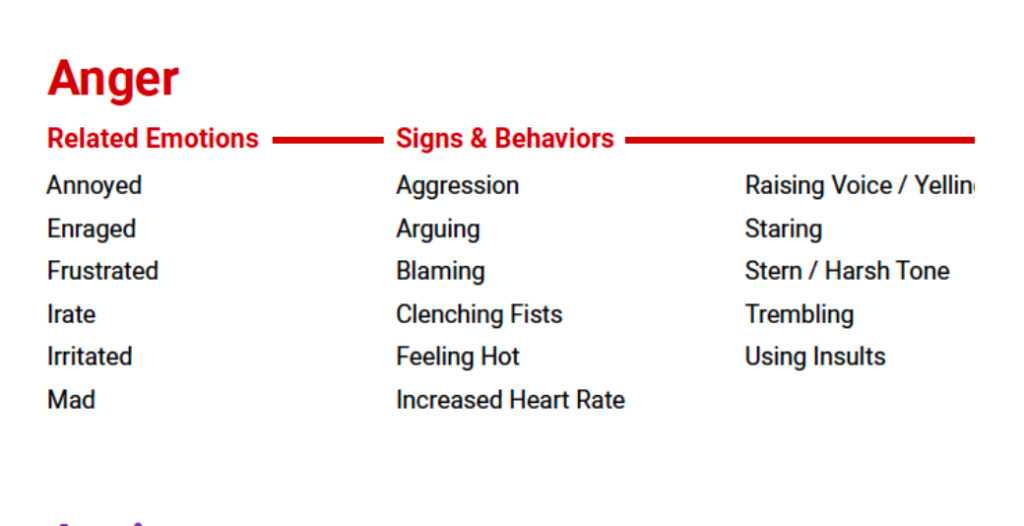

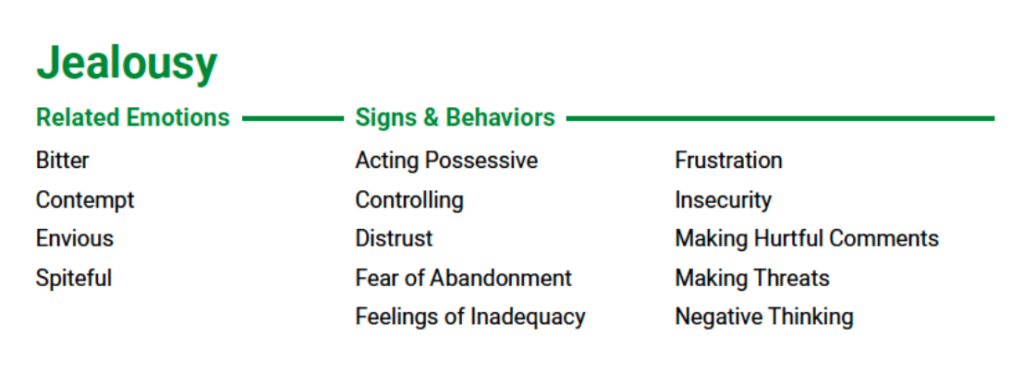

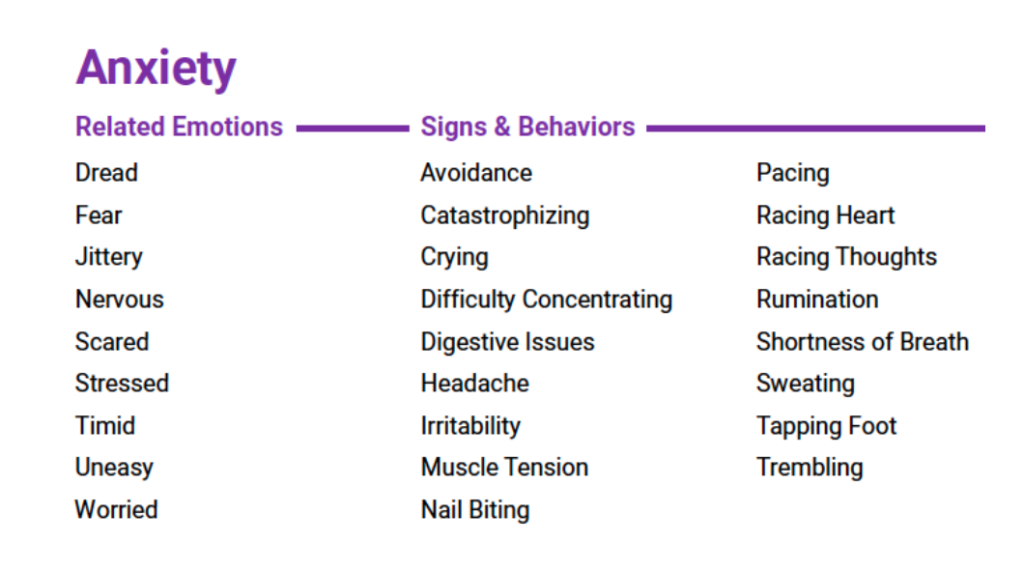

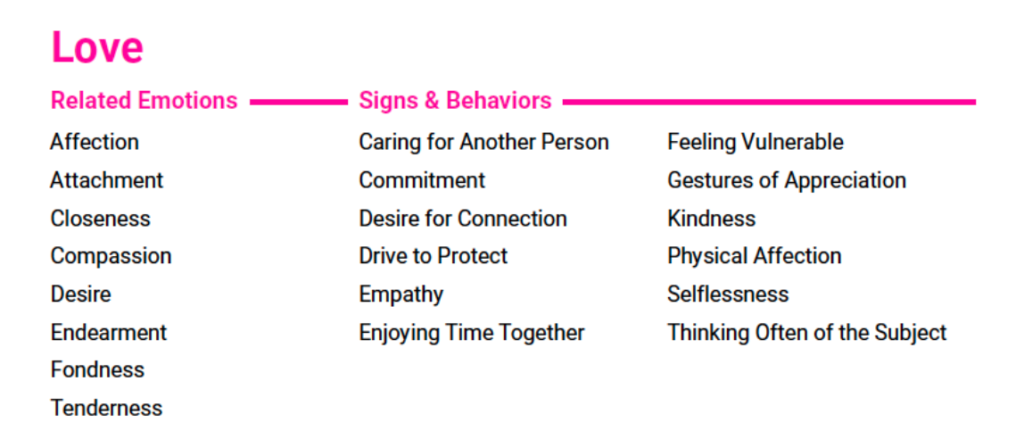

Design. The experiment was conducted as a between-subjects design where participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions. The independent variable, journaling utilization, existed in two conditions: daily activity journaling (Group 1) and emotional-awareness journaling (Group 2). Empathy, the dependent variable, was operationalized according to the Empathy Quotient (EQ) Test for Adults and the Short Stories Questionnaire (SSQ) for Adults, two different measures of empathy (Appendix A). All participants took the EQ and SSQ tests and submitted the questionnaires for scoring. This pretest provided baseline empathy scores to compare later posttest empathy scores to, allowing for an analysis of empathy change following the experimental manipulations. Both conditions were then instructed to journal nightly before going to sleep for the duration of one week. Participants in Group 1 were instructed to utilize their journal to recall daily activities and served as the control group. Group 2 participants were instructed to journal regarding their emotional states throughout the day and served as the experimental group. A list of different emotions and associated signs and behaviors were also provided to Group 2 participants (Appendix B). They were encouraged to refer to the chart to precisely identify and label their different emotional states when journaling each night to promote deeper emotional-awareness and reflection. All participants were instructed to journal for the same amount of time each night (10 minutes) and for the duration of one week to control for potential confounding variables. At the end of the last day of journaling, both groups retested on the EQ and SSQ tests and submitted them for scoring. The pretest and posttest scores were then compared and analyzed across conditions for significant trends.

Results and Discussion

It was anticipated that the journaling utilization would mediate the impact of journaling upon empathy scores. We hypothesized that the increase in empathy scores would be significant for the emotional-awareness condition (Group 2) compared to no significant change for the daily activities condition (Group 1). Across the emotional-awareness condition, the resultant data was consistent with the original hypotheses. Group 2 participants improved by an average of 2.35 points for the EQ test (approximately 3.00% improvement) and 1.0 point for the SSQ test (approximately 5.0% improvement). These were considered to be a marginally significant and significant results, respectively, observed for almost all participants in Group 2. For the daily activity journaling condition, SSQ scores were fairly consistent with an average increase of .33 point (approximately 1.65% improvement). This change was deemed nonsignificant, and corroborated previous expectations. However, the EQ scores for the daily activity journaling showed an unexpected decrease; on average, participants in the daily journaling condition showed a decrease of 6.17 points from the pretest to the posttest (approximately 7.71% decrease). This was an unexpected result demonstrated across over half of participants in the control condition. SSQ and EQ scores are summarized in Table II.

| SSQ | Mean Scores | EQ | Mean Scores | |

| Pretest | Posttest | Pretest | Posttest | |

| Group 1 (Control) | 8.00 | 8.33 | 54.67 | 48.50 |

| Group 2 (Experimental) | 12.75 | 13.75 | 48.75 | 51.10 |

The increase in empathy scores observed for participants in the emotional-awareness condition was consistent with our hypothesis. While this result could be attributed to the retest effect (also referred to as the practice effect) as the exact same SSQ and EQ tests items were administered twice, the effects would have been universally applied to both conditions. As the only marginal or significant increases of EQ and SSQ scores were observed for Group 2, the score improvement is more likely due to the effects of practicing emotional-awareness journaling than to previous exposure to the test questions.

Across nearly half of the participants, average scores on the EQ tests (44-50) and low scores on the SSQ test (5-8) were paired together for a participant, which is not typical for the empathy tests. The inconsistent results are unexpected, as these items typically have high concurrent validity. However, the SSQ and EQ differ on the number and nature of items presented, which may pose an explanation for this occurrence. The EQ relies upon self-report of how strongly a participant identifies with a list of 40 provided statements (Appendix A). The SSQ consists of ten different stories and corresponding responses, of which participants are asked to identify any responses could be perceived as upsetting. Additionally, whereas the EQ is an American test, the SSQ was created by the University of Cambridge in the U.K. As the majority of study participants were American undergraduates, it is likely that British phrases in the SSQ impacted comprehension and led to lower test scores. The combination of the different methods of assessing empathy and the language differences across the test likely contribute to the low concurrent validity observed.

The substantial decrease in EQ scores for the daily activity journaling was unexpected and consistent across most Group 2 participants. It is unlikely that the act of daily activity journaling was a major cause of the decrease in EQ empathy scores. Rather, this was likely caused by a careless task approach on the self-report, as traditionally EQ scores show high test-retest reliability over the course of 12 months ( “The Empathy Quotient (EQ) for Adults”, n.d.).

Conclusion

Previous studies indicate journaling promotes the improvement of empathy skills. This research was supported by the results from this study, as the emotional-awareness journaling condition showed an increase in scores across both the EQ and SSQ tests. The empathy score increase deemed marginally significant or significant were only found for the emotional-awareness condition and not for daily activity journaling. This implicates the importance of self-reflection in promoting empathy, as empathy scores only increased when participants were instructed to foster emotional-awareness by utilizing their journaling sessions to recognize and label their emotions. This study suggests it is not the act of journaling itself that is significant, but the way in which it is utilized to promote self-reflection that has an impact upon empathy.

The resulting trends demonstrated that journaling focused on emotional-awareness was a likely contributor to the observed increase in empathy scores across the EQ and SSQ tests. However, further research directed specifically at the practice of journaling is needed to further support previous research findings and assert whether journaling is a major cause of empathy improvement. Additionally, the degree to which empathy scores can improve through journaling remains unexamined. The small sample size and the limited duration of the experiment posed limitations that should be considered and improved upon for future study, as a larger participant pool and a longer period of journaling could lead to more substantive results. Likewise, further study is necessary to determine which manner of journaling is most beneficial for the improvement of empathy.

Works Cited

Beitel, M., Ferrer, E., & Cecero, J. J. (2005). Psychological mindedness and awareness of self and others. Journal of Clinical Psychology,61(6), 739-750. doi:10.1002/jclp.20095

Davis H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,44(1), 113-126. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

Dymond F. (1950). Personality and empathy. Journal of Consulting Psychology,14(5), 343-350. doi:10.1037/h0061674

Gerace, A., Day, A., Casey, S., & Mohr, P. (2017). ‘I think, you think’: Understanding the importance of self-reflection to the taking of another person’s perspective. Journal of Relationships Research,8. doi:10.1017/jrr.2017.8

Jamieson, Krupa, T., O’riordan, A., O’connor, D., Paterson, M., Ball, C., & Wilcox, S. (2006). Developing empathy as a foundation of Client-Centred Practice: Evaluation of a university Curriculum Initiative. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy,73(2), 76-85. doi:10.2182/cjot.05.0008

Patton T. (2019). Engaging Methods to Teach Empathy: A Successful Journey to Transformation(Doctoral dissertation, Union University School of Education, 2019) (pp. 1-160). ProQuest LLC.

The Empathy Quotient (EQ) for Adults. (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, 2020, from http://disabilitymeasures.org/EQ-Adult/

Appendix A

Sample Items from the Empathy Quotient (EQ) Test for Adults

THE CAMBRIDGE BEHAVIOUR SCALE

Please fill in this information and then read the instructions below.

Name:……………………………………………………………………

Today’s date:……………………………

How to fill out the questionnaire

Below are a list of statements. Please read each statement very carefully and rate how strongly you agree or disagree with it by circling your answer. There are no right or wrong answers, or trick questions.

| 1. | I can easily tell if someone else wants to enter a conversation. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

| 2. | I find it difficult to explain to others things that I understand easily, when they don’t understand it first time. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

| 3. | I really enjoy caring for other people. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

| 4. | I find it hard to know what to do in a social situation. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

| 5. | People often tell me that I went too far in driving my point home in a discussion. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

| 6. | It doesn’t bother me too much if I am late meeting a friend. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

| 7. | Friendships and relationships are just too difficult, so I tend not to bother with them. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

| 8. | I often find it difficult to judge if something is rude or polite. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

| 9. | In a conversation, I tend to focus on my own thoughts rather than on what my listener might be thinking. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

| 10. | When I was a child, I enjoyed cutting up worms to see what would happen. | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree |

Appendix B

Wolf Totem by Jiang Rong (Trans. Howard Goldblatt)

a book review by Dana (the photo is of coyotes, not wolves)

A beautiful, fascinating, exhilarating, tragic story of the way the Olonbulag grasslands of inner Mongolia were quickly ruined by the short-sighted and hubristic agents of “progress.” As one official says impatiently, we don’t need wolves to control gazelles and marmots and mice when humans have guns and trucks to eradicate all of them.

During the 1960s Cultural Revolution, “Old Man Bilgee” teaches the visiting Han Chinese student Chen that “wolves are the divine protectors of the grassland” (20, 123). The real source of wealth, what’s at the bottom of everyone’s livelihood, is the grass, which is put at risk from rabbits and marmots and also (especially) gazelle and horses and the fact that Han (outsider) farmers are quickly replacing Mongolian (native) herders. The grass is “the big life” and all the others lives, including wolves and humans, are “little lives,” dependent on that big life. The grass is “fragile,” “miserable,” has “shallow” roots in “thin” soil, and “cannot run away” (45). And “when you kill of the big life of the grassland,” says the wise Bilgee, who the visiting students call “Papa,” “all the little lives are doomed.”

But the inexorable pride, ambition, and blindness of people working in a punishing bureaucracy mean that the expected tragedy unfolds. This “semi-autobiographical novel” is a detailed, almost anthropological study of the problem with messing with balanced ecosystems. It’s a warning tale about thinking humans can easily re-engineer nature, changing the rules so we get all the advantages with no downsides and as little effort as possible. I think it’s a tale of optimization using models that fail to take everything into account. It’s also a tale of what happens to people in this situation: they don’t need dogs anymore so they no longer have big, enthusiastic families of dogs around them; they get satellite dishes; they have less community and less purpose. As Rong writes, “After the disappearance of the wolves, the sale of liquor on Olonbulag nearly doubled” (494).

It turns out, of course, and again, that nature has already solved complex problems, and that human short cuts to prosperity (because we don’t want to put up with the trade-offs nature demands) fail because we barge into new situations, ignore the wisdom of the knowledgeable people who already live there, and ignore most of the variables in our eager, optimistic simulative imaginings. One resource that helps engineers become more aware of the variety of ways nature might have already solved a problem that they are contending with is AskNature.com (https://asknature.org/), which describes “biological strategies” for problem-solving that are already in action.

For one, then, this book is about geo-engineering, a kind of terraforming that has happened all over our earth, a simplication that seems nice and straightforward until we see all the value we’ve lost. That’s a warning.

On the other hand, this is a story about grass. One might hear similar, more local, estimations about the value of grass from Virginia farmer Joel Salatin (who figures prominently in Michael Pollan’s book The Omnivore’s Dilemma). They both make me want to change my “Food not lawns” bumper sticker to another that says “grasslands not gardens” (and I love nothing more than a garden!).

I will add that this is a beautiful book and that it let me spend days on the grasslands with the wolves and swans, with thoughtful, morally conflicted people, and with their exciting adventures in that stunning landscape. The book has some strong views on ethnic character, which I translated into ideas about the way landscape fashions cultures and people. It shares a deep respect for the wolf totem and for Tengger, the sustaining sky that gives them all things and to which they hope to return at death. And finally, it let me spend some time not just in China and Mongolia, but in the minds and hearts of people there.

Jonathan Bunton

May 14, 2020

Abstract

Empathy is a core character trait that is often forgotten in the realm of STEM students. It is a deeply humanizing characteristic that allows us to understand and connect to other people, like an emotional ethernet cable. In this work, I discuss some figurative “empathy bicep curls” that I used to develop empathetic habits. In particular, I explored connecting to fellow lab-mates in a strictly non-lab setting, through casual check-ins and weekly video calls. During these weekly calls, I tried to read people’s moods, like a mystic crystal ball reading of green-boxed video streams. I used this mood-reading to engage everyone, sowing the seeds of a deep support system in both my lab group and my larger network of friends.

Introduction

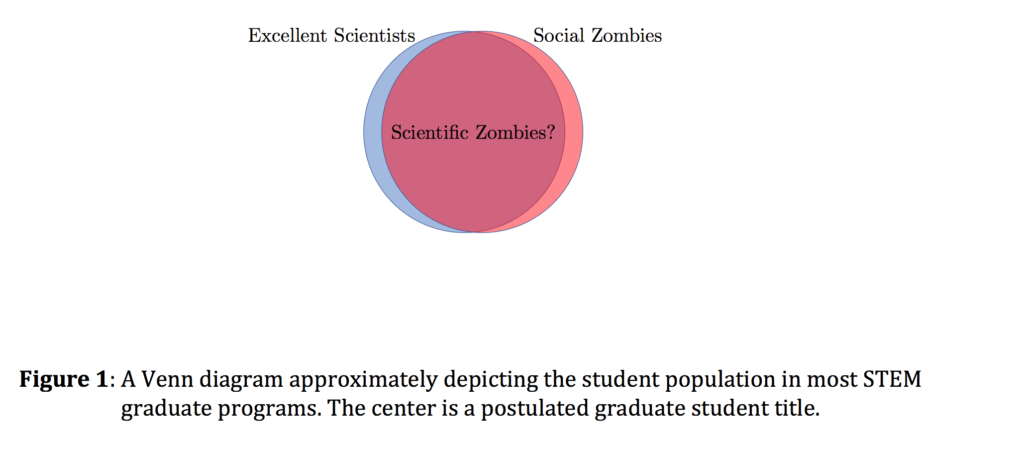

Graduate school in STEM is excellent at producing two types of people: excellent scientists, and social zombies. Moreover, if we were to draw a Venn diagram of social zombies and excellent scientists in a STEM graduate program, we might guess the result would look like nearly a solid circle (see Fig. 1).

This result is of little real blame on anyone involved–graduate school inherently requires an immense amount of research and work, which quickly eats away time. And graduate students are generally happy to do this work, with little regard for their mental health. If this statement seems doubtful, a quick cursory glance through some of the top posts on various forums reassures that working until burnout is a common feeling.

A major part of this problem arises because graduate students stop treating themselves and their lab mates as real people. This isn’t to say that lab meetings suddenly become awkward menageries of mythical creatures, but more that students forget how to interact with each other on a simpler, person-to-person level.

The goal of this experiment was to remind myself and my lab of the importance of these sorts of interactions. I often use this “Everyone Poops!” style of reminder to keep myself humble, and also to muster the courage to talk to people. It’s the same method I used when I asked my girlfriend to date me while standing in a unitard at the National Mall. (The deeper reasoning for this picture is an excellent story that I’d be happy to explain another time.)

The “empathy workout” that I felt aligned with the importance of humanizing people, and in particular graduate students, was item 12 on the assignment list for the empaty experiment:

Make at least one personal contact with one of your fellow students (or lab-mates or coworkers) each week. It can just be “hi, how are you doing?” or you can share a personal story, one that you think the other person can relate to and that may then help them connect to you better afterward (Alan Alda, If I Understood You, Would I Have this Look on My Face?, 146-7).

Using this suggestion as a guideline, I doubled down on these efforts: I organized a weekly lab video call that did not include our professor, and I reached out weekly to a student in my lab who is quarantining alone.

My lab is fairly social, especially when compared to others in our area. Before the quarantine came into effect, we often had small social gatherings that were unrelated to the lab itself. We played games, went for drinks, even played instruments together.

During our time apart, however, I felt we needed something to remind us that we are more than just “work associates,” we’re friends. And moreover, that we are all here to lean on in these odd times. More than anything, I argued to myself, this process would humanize us, and remind us that we are all just people coping as best we can. This “humanization” of myself and my lab mates is arguably the ultimate goal of empathy: to understand and relate to each other, despite cultural, social, and computer screen divides.

Methods

In the current state of quarantine, video calls are the new norm. They pranced into everyone’s homes as though they had been there all along, silently creeping into our offices, our kitchen tables, and even our closets. It’s a sad state of affairs, but it is the world we live in. It is about as close as we can get these days without breaking Center for Disease Control guidelines.

Knowing this situation, I organized a two-pronged approach to this empathy exercise:

1. Reach out to one lab member a week who I know is quarantining alone.

2. Organize a group video call, outside of normal lab meetings, to keep everyone connected.

There are several international students in my lab, which means there are several friends of mine who are stuck alone in studio apartments, away from their families, during the quarantine. I sent them messages weekly–some were more conversational than others–and tried to gauge how comfortable they felt talking to me. The goal with this experiment was to not only provide a support system for these students (and myself), but to try and understand the immense difference in quarantine scenarios between us.

With video calls, I sought to keep our lab community close through quarantine. We needed a space where we were allowed to be just people, not research machines. To further this goal, I included several members of our extended friend group, to keep the call from feeling too much like a repeat of each week’s multi-hour lab progress report. I tried hard to note how everyone felt and seemed to be handling things both when talking, but also when just sitting on camera. Did they seem distracted, nervous, bored? Aside from the goals of better camaraderie, I wanted to learn to read audiences in video calls, because this skill seems to be invaluable these days.

Results and Discussion

I followed this exercise for approximately four weeks. This meant four weeks of reaching out to a person alone, and organizing a non-work video call.

Over the course of just sending messages, I learned more about my lab-mates who were living in isolation. Not just what they were working on, but what they did in their free time, and what they thought about while relaxing at home. This slightly deeper connection helped me understand them, and I’d argue to be a better friend.

I learned that one of my lab mates has become a plant parent several times over, by snagging and re-planting pieces of several neglected plants around his apartment complex. In an entirely opposite direction, he had become immensely invested in a series of war documentaries. By proxy, I learned a lot about the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War from an Argentinian engineering graduate student.

I also learned all flights to Argentina were cancelled, and he had nowhere else to go. He said his plants helped keep him sane, and he had a strict regimen of “class times” to divide his workday. His admission of this was sobering, coming from a person who is typically the happy-go-lucky type.

Meanwhile, I learned that another lab mate was extremely okay with being alone, because he was a less social person to begin with. I learned he had dug up some archaic and unused programming languages and trying to re-learn them. Some people are born masochists, I suppose.

Though not necessarily massive leaps, these conversations were enlightening. I spend so much time connected to these people, since my lab is basically a second home. But small conversations like this–especially during such uncertain times–help build us together into a support system.

The video calls, by contrast, started slow. Nearly everyone in my lab had used Zoom for our cross-campus research meetings in the past, so we all felt some odd pressure to stay professional. This pressure manifested itself with awkward fits of “So how is research going?” and “What’ve you been working on?” when conversation lulled.

I did my best to break these habits by instating a no “shop talk” rule during these calls. These calls were meant to be our lab utopia–a free space for us to be normal people, not just runners on the graduate research hamster wheel. To further limit “shop talk,” I invited some friends from outside the lab to join. These people helped set a distinctly different tone than in our typical weekly lab meetings.

The calls eventually became something expected—friends would text to remind me to send out invites to the week’s call. If anyone missed, they would later check in with me to see if everyone was okay, and also how the call went. It became a weekly pulse check on everyone in the lab: are they here? If not, has anyone heard from them? Especially in this time of quarantine, these weekly calls seemed to be a moment for us to take stock of the lab as people, building a tighter network of people to depend on.

I also tried to identify the mood and level of engagement of different people in the calls, especially when not talking. This meant learning a whole new set of social cues, watching people in a small green box as they scroll through their phone, or nod absentmindedly against a shimmering and pixellated “The Office” backdrop. The audience-centered empathy skills for in-person speaking are familiar and easy to read after much practice, but translating them to Zoom calls feels like trying to infer typical lion behavior from my dad’s house cat “Simba.”

I used these mood gauges to try and engage everyone as best I could, teasing people into un-muting microphones and turning on video streams. “We’re good enough friends to hear each other’s static,” I reassured everyone.

As the weeks went on, I found it easier to identify people who needed to be involved. This process felt like re-learning elementary lunchroom etiquette, remembering to invite the sad-looking boy sitting alone to come eat with everyone else. However, unlike the sad-looking boy in elementary school, people in Zoom calls are usually quite content to sit looking at their cell phone instead of talking to a computer screen of ten floating heads.

Learning these mood cues through video call reminded me a lot of the initial test we took, reading emotions through just eye expressions. I think in future weeks, I could further my video calling exercise by trying to assign these sorts of emotion labels on my lab mates while in the call. Ultimately, I may continue this experiment with several small variations, with my friends as the unknowing test mice in my empathy laboratory.

Conclusion

Empathy is an immensely useful characteristic of effective communicators, researchers, and friends. It is an incredible humanizing tool that allows us to connect with an audience, a reader, or a group of friends. I took this experiment as an opportunity to humanize my lab environment, by initializing weekly video calls to keep touch during the quarantine.

Though video calls are common these days, my lab only ever participated in one all together on a regular basis: research meetings. While important, these meetings are a rapid- fire pop-quiz on the science we worked on the past week, with few pauses to connect as people. I felt my lab could retain and strengthen its own empathy support system by having a special time set aside where we were allowed to be people, and talk to each other as people.

These weekly calls started as awkward chats, but eventually became an anticipated occurrence. It’s easy to forget through all of the research meetings and classes that under it all, our lab is also a group of good friends. I hoped and felt that these calls reminded us of that fact, while strengthening our empathy networks.

My own empathy skills could use continued work, and I plan on using these weekly calls as a training ground for reading audiences over video call. As we brace ourselves for an online fall quarter like the Starks preparing for winter, these sorts of skills seem more invaluable than ever.

Even more so, I need to retain the ability to connect to other people, lest I emerge from quarantine a full Neanderthal, unsure of how to appease the lab group tribe.

Scientists have as much right to poetry as everyone else! I think that, and my students have said as much. The amazing stuff that scientists figure out about the natural world is thought-provoking and sometimes leads to a poem. Here’s one of mine. If you write one, maybe share it with me?

An ant colony as a body–

one rock, aphanite, united.

One ant goes missing, no big deal, but

one missing hydrocarbon in a set of three

changes everything.

The dead, then, are not dead;

enemy, friend, parasite, slave maker, family member, burglars

are not just nemy riend arasite lave aker amily ember and urglars

they are unnoticed, welcomed.

Aphaeresis matters

nd no error detection codes lead to baneful miscues.

But Wilson says, “One ant alone is a disappointment.”

Think of the superorganism, and then see multitudinous redundancy,

the success of the species.

But don’t look too long, or you’ll see yourself, expendable,

an useless ember, a guttering urglar, nemy riend.

—Dana Cairns Watson

Writing is a form of thinking, and today I want to think about Mount Everest and NASA. Many people were horrified recently to discover that there were crowded lines on the safety ropes to summit Mount Everest. (And we readers at home, looking at the photos and hearing the stories, were probably much less horrified even than the people on the mountain, people who’d worked hard to get there, who had paid a whole lot, and whose lives were at risk because of those lines.).

We should really spend only a small proportion of our time on the consumption of media, or at least we should devote a significant amount of our attention to production. So argues Clay A. Johnson’s The Information Diet. I completely agree, and yet I haven’t usually kept the habit. Last summer, I even gave myself I pass. I said, “I’m not going to write anything.” And I didn’t. I still gardened, cooked, came up with a new syllabus for an old class. I probably wrote a poem or two, some journal entries, some letters. There was some production, yes. But why not, this summer, try to avoid snacking on inputs so I have time for the main course, my own writing? And some of that writing will be short, snack-like, while I decide what I should really be working on!

In The Guardian’s “In Focus” podcast, “Death, carnage and chaos: a climber on his recent ascent of Everest,” (3 Jun 2019), a climber describes how people at that altitude can’t think straight, how they are each barely able to survive on the oxygen they carry, and how vulnerable and injured climbers cannot expect to be cared for by the others. They are all stuck on the same safety line, but everyone is at the end of his rope. This has always been true on Everest, of course, but now inexperienced climbers, unfit climbers, plain old (or young) rich climbers, expect that their money can get them to the top. And the others cannot always help them. Money doesn’t matter there. Everest is still free of the unctuous servility that can be bought by the winners of the capitalist game. Put another way, to support our own civility and humanity, we have to remain at the altitudes that can support life.

Now (well, as early as just next year, 2020) NASA is thinking of charging 58 million dollars (plus $35,000/day) for a trip to the International Space Station (Los Angeles Times, 7 June 2019). But I can’t help thinking of Everest. If something goes wrong–if people have to survive by their wits and what they know of space, science, and technology (think The Martian), or if there’s just a simple shortage of oxygen (think Everest 2019)–then will the “guest” astronauts survive? Even people with the greatest human gift of compassion, free of the psychology of capitalism, will have to calculate that the survivors need to be able to, well, survive. Keeping the guests alive for another day will not solve the longer-term problem of getting the oxygen production back working, getting the ship’s communications up, getting the ship home to earth, or whatever else needs to get done. In short, sending amateurs to space is a lousy idea.

That’s my big idea for the day. I wrote it down. And here’s what I think it has to do with my new and broader conception of Writineering:

Engineering and scientists are sometimes reticent to speak up when the topic is not their area of expertise. I’ve asked ECE graduate students to read a bit on the climate crisis, for example, and then I’ve asked them to opine. They generally won’t. They think it’s out of their area. And yet, if anyone outside an Earth and Space Science Department can understand, evaluate, and appreciate the data, it’s another scientist or engineer. Becoming a specialist does not mean that you must voice no opinions on other topics. You are a citizen, a brainy one who asks important questions and knows how to go about answering many of them. Please, then, share your thoughts with the rest of us. We need you to weigh in!

Here’s a new version of Writineering, now helpfully supported by UCLA and intended not just for graduate students in engineering but for writers at all levels who are eager to explore science, engineering, or technology. Academic writing is at its best when it borrows from public science writing, and writing for the public achieves more and better ends when it borrows careful, ethical data collection, analysis, and referencing from academic writing. We have many shared roots; good writing identifies its sources; and the best writing has an author’s thumbprint visible (see photo). As Jaron Lanier writes in You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto, “there is no evidence that quantity becomes quality in matters of human expression or achievement. What matters instead, I believe, is a sense of focus, a mind in effective concentration, and an adventurous individual imagination that is distinct from the crowd” (50). And so while this is a software-dependent website, please remember that it’s for people, by a person. “Keep that in mind when writing anything” is recommendation #1.

S and I talked via Google Hangouts at lunchtime on a Sunday. While my camera was poorly positioned, showing the bed (made; phew!), the mess on the dresser, a mirror weirdly reflecting the window behind the laptop, and me with my wet hair (how did I forget this was a video call?), hers only showed her face and the upper corner of a white room. She clearly does this more than I do, already revealing her professionalism. This state of affairs in itself highlights one reason that I wanted to have this conversation: what do professional engineers really need from academics like me?

S got her PhD a few years ago, and we know each other because she took EE 295 and participated in a short-lived EE Book Group. (We met for four or five quarters, and then people graduated before we’d repopulated the group.) She sees herself more as a mathematician than an engineer, and after two years in industry, she’s now in the first year of a two-year post-doc. She’ll soon begin applying for faculty positions.

As part of the run-up to the application process, S says she is trying to get invited to give talks at many universities, even if they are not hiring. She reminds me that “these talks have to be understandable to everyone in the audience, which can be tricky since most people aren’t working on remotely the same thing as you are, yet still need to feel included in the talk.” And this statement reminds me of what my neighbor, a UCLA physiology professor said later on that same Sunday when she was discussing a job candidate: “he didn’t connect the dots between his work and why I should care.”

But S sympathizes with the student experience, and the difficulty of moving from details to generalities. “School’s set up to put you in that tunnel vision,” she says. And she means this in more than one sense: school makes us focus on our area of expertise, “but it can also make us feel incompetent, since our ‘product’ isn’t directly benefiting anyone (yet).” When we enter the “real world,” it’s refreshing to see how competent we really are, if we’ve retained the skills we need for that broader world of work.

S benefited from going to an undergraduate engineering school that assigned many open-ended projects; she feels that she “would have been more cautious” if she’d gone through a more traditional program. She says that the projects “brought me out of my shell” and gave students more power of “self-determination.” Because it was a small school, she got “a lot of personal responsibility.” And because of an extracurricular role as a yearbook photographer—what sounds like the yearbook photographer–she says that she

had to go to all these events that I never otherwise would have gone to, just to take photographs of people. It really got me out of my shell; at first, I was afraid even to make phone calls to order pizza, but by the end we were all way more confident approaching strangers to get interviews for random projects.

In all these ways, S’s experience highlights the value of broadening one’s horizons, participating in many activities, meeting and talking to new people, and trying to communicate across disciplinary borders and other (often self-imposed) boundaries.

Another way to do both these things—explore beyond boundaries and communicate across them—is to review papers: “Be a reviewer for conferences, even the ones you don’t submit to,” S recommends. It’s valuable experience. During her time in industry, she did a lot of this, and she also had to give many “’broad picture” and “state-of-the-art” presentations for CEOs at the company. In one email, she writes:

Giving survey presentations was really great practice for me, because (1) it forced me to read a lot of papers on subjects I didn’t really understand and pull out the few things I thought would interest a general audience, and (2) it forced me to communicate to as broad an audience as possible. When I went back to academia, I realized this was a key skill that you don’t really learn in school—not that they don’t know how to prioritize their audience, but they’re not really under a huge amount of immediate pressure to do so.

One thing that surprised me about S’s industry job is that “they tried to figure out what [she] wanted to do and let [her] do it.” Not all industry jobs would be like this, but having your PhD probably puts you in a great position to be an explorer and motivator rather than a drudge at work. “Drudge” is probably the wrong word, since it means the person who does the “tedious and menial” work. But sometimes graduate students get in the habit of working alone in their cubicles. That alone-time can produce great work, but it’s under-appreciated if done in silence. It might not even be as useful as it could be if it were done in tandem with other people’s knowledge and goals.

S was surprised to discover that people interrupt talks in industry, and she’s productively imported this to her new academic position. She says, “at a company, people are really obnoxious and stop you every five seconds (because they’re your boss).” She adds, “if people don’t interrupt you, then you know you’ve had a bad meeting.” The advantage of being interrupted with questions is that you “get a better sense of your audience”—both what they know and what they care about. So instead of trying to overlook, ignore, or fill in the blanks herself as she listens to talks in her current university position, she’s become “the obnoxious audience person who keeps making the presenter stop and clarify things” and says that “actually, a lot of people told me this as a compliment!” I remember S’s digging down into some of our responses in the book group, so I can easily imagine the tone of her questions: not at all obnoxious, but not soft. Often, her questions and comments made the rest of us rethink or at least more carefully state our ideas.

I wanted to know what these jobs are like. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that a post-doc (or at least this post-doc) spends her time “reading papers and writing ideas.” She adds, “One thing that post-doc freedom allows you to do is to have three-hour meetings with other colleagues to discuss random ideas, which I do with another postdoc every week.” There’s also some teaching (this year, S gave two lectures; next year, she’ll teach a whole course) and “a fair amount of mentoring.” So far, she’s not had to do much grant writing or traveling.

About the mentoring, S says,

I don’t really mind mentoring because . . . working one-on-one . . ., I find it easier to engage with the student and make sure we really exploit his or her talents and ambitions. Actually, we have one student here who is really kick-ass. He’s only a first-year master’s student, but he decided he wanted to learn really hard subjects by running reading groups and teaching us. So whenever I have a hard problem that I don’t really have time to look at, I just give it to him over Slack, and he answers it for me later that week. (Does that make me abusive?)

I’d say no, and here’s why. S’s attention to the specific “talents and ambitions” of each student suggests that her need for information and this student’s goals are fully aligned. She’s giving him exactly what he needs to develop in the ways he wants. And she’s giving him what she has already said is valuable: the chance to read many hard papers, practice pulling out the ideas that are useful for a certain problem or audience, and practice explaining them to others.

Because S is successful and spirited, I wanted to pass on some sense of her “philosophy of life.” While resisting offering one, S emphasizes flexibility and gratitude. Because “the whole process” of the job search is “unpredictable” and moves at erratically slow speeds and big leaps, “there really is an element of faith” and “you just have to try your best and try not to read tea leaves.” In her case, she spent six months working diligently to get a postdoc position, “negotiating with various professors” and “testing various sources of funding, etc.” and then, “out of the blue, a prof contacted me and almost immediately the offer went through.” S summed up her philosophy this way:

Maybe just try not to take anything too seriously, and try not to be hurt when things don’t go your way? It’s easy for people who have very high aspirations to be very upset when they see people achieve dreams in ways that seem like pure luck, but the fact of the matter is we are all really lucky to be alive, well-fed, and generally safe from war and famine. Actually, there was a podcast about this, which said it really well: we always feel the headwinds, but we never appreciate the tailwinds (a biking analogy!). So maybe my life philosophy is “don’t forget the tailwinds!” Or, less pessimistically, there’s way more in life to enjoy than can be found at the end of a career path!

Once again, her message is to take the bigger picture into account!

I have a lot of what I consider great ideas for my engineering communication class, but I just don’t have the time to use them all. When I try, the course becomes a crazy quilt (and I mean “crazy”) of activities and assignments. It becomes way to complicated for students to keep track of. If you’re not living it now, remember or imagine the life of a graduate student in engineering at UCLA. You are pulled in many directions, at the beck and call of your advisor, feeling squeezed between a set of challenging expectations, and trying to meet multiple deadlines. And then I show up to teach your required writing course, all “la-di-da, this is going to be so fun,” BUT you have to check the course website every few minutes to keep up with a large set of mostly-not-very-time-consuming but surprisingly many assignments. That’s just too high a cognitive load to add to the ones these students already have. So, on the course front: simplify, simplify, simplify. And here, at Writineering: get all those other ideas off my chest. If you have the time to try some, alone or with others in your labs, you’ll get multiple positive outcomes. And you’ll be saving some stressed graduate students from my inflicting them with these ideas now! So, just to get you started, here’s big, huge suggestion number one: Read Alan Alda’s book If I Understood You, Would I Have this Look on My Face: My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating (2017). And then try out some of his suggestions. While you wait for the book to arrive**, you can start trying to identify the emotions of the people you meet throughout the day. Nothing else, just spend a moment pondering their expressions and behaviors, and then think “grumpy” or “tired” or “cheerful” (or whatever else seems appropriate). Why? For one, you’ll start to notice how often you just barge into a conversation without paying any attention to the other person’s receptivity or mood. Second, you’ll be developing a habit of attention. Third, you’ll probably get better at identifying moods, since your subsequent interaction will give you feedback about how accurate you were. And fourth, you’ll be able to choose your words more appropriately, and have a more productive conversation, with this information at hand. Let me know if you find other benefits, too! ** A note about getting books. I have a lot of ways of accessing books, so I’m going to describe them here. You can probably find similar resources where you live, although the collections might not be as huge. First, I can order it new or used online. This is great: you own the book! But you also have to find shelf space for it, and you have to wait a couple of days. (Of course, you could read it, and then start passing it around to your friends and colleagues—this leads to fun conversations.) Second, I can go to Hoopla and connect to the Los Angeles Public Library, and they usually have the e-book or an audiobook that I can download. I can also go directly to the LAPL website, find the book, and it’s often available by download through Amazon or I can ask them to deliver the physical copy to my local branch library. If they don’t have it, I can check the e-resources of other local library systems (in my wallet are cards for the Beverly Hills Library, the Pasadena/Glendale Library, the Santa Monica Library, and the Culver City Library, but between LA and Beverly Hills, I can pretty much access what I need). You, too, can probably join more than one library system near you. Third, I can use the UCLA Library and even interlibrary loans to get almost any book for free. Sometimes interlibrary loans are a long wait, however.

Often, engineering writers tell me that they do not need to define their terms because their audiences know what they are talking about. So this week, I did an experiment in two classes, one of 18 students and one of 23 students. They were to write down words and phrases that they need to use when discussing their work. And then we passed the lists to every other person in class, who each marked the words they did not know. They might have heard them before, but they would have to look them up, or they’d feel that the term was vague or ambiguous. In short, they’d like it to be defined. Here’s the data.

There were close to 400 unique terms, and about half of them were familiar to most people (no more than two people, or about 10%, were confused by them). But about half confused more people than that, and some confused over 60% of the people in the room.

I want to emphasize that everyone was a PhD student in the Electrical and Computer Engineering Dept. at UCLA. They’ve all passed their preliminary exam. They are the most informed audience one might hope to have, beyond one’s lab partners. Yes, we sometimes talk to people in our very specific fields, but others should be able to understand us, too! When you go ranging around the literature for ideas, you’d like to feel that the authors are trying to help you!

I hope to continue this exercise with future classes, so I can collect more data.

One note: if there are several numbers to the right of a term, that means that more than one person put it on his or list list. In the smaller class, no term was listed by more than two people; in the bigger class, some terms were listed by four people.