A research article by Jessalyn Smith

*Trigger Warning: this article contains content related to domestic violence*

Abstract

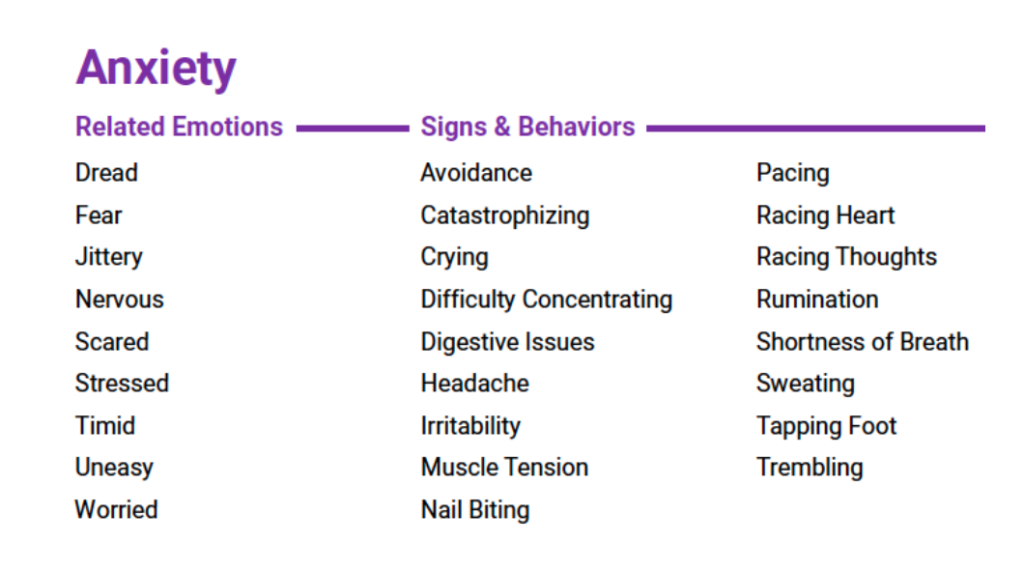

An Emotional Support Animal serves to alleviate the effects of an emotional disability. For someone suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, the presence of such a companion can lead to a reduction of symptoms and a greater feeling of security. As more people are prescribed Emotional Support Animals, it is important to test how these therapeutic tools could most effectively be utilized. In this case study, I tested my mood and stress response before and after playing, walking, and cuddling with my emotional support animal and recorded my thoughts in a journal for each activity. My moods, physical symptoms of stress, and thought processes were then analyzed to monitor the improvement across each category. While all activities showed benefits to my mood, playing with the ESA showed the greatest improvement. Additionally, there were no physical responses to stress noted after the playing sessions. However, the changes in my writing characteristics and observations were consistent across all forms of activity. Based on the data collected, active interactions with an ESA provided the most useful form of self-therapy for the subject.

The Effect of Emotional Support Animals on the Mood and Stress Response of a Person with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops after a “shocking, scary, or dangerous event” and can lead to flashbacks, difficulties sleeping, avoidance of triggers, and memory issues among several other debilitating symptoms (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, n.d.). The Vietnam War is widely associated with the first identification of PTSD as a mental disorder, and the term “post-traumatic stress disorder” was published by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980 (Crocq, M. A., & Crocq, L., 2000). However, this was not the first instance of PTSD as it likely went unidentified in trauma survivors long before its formal identification. Although psychologists started studying the disorder as “shell shock” in combat veterans, the term has since changed and expanded to include victims of abuse, assault, neglect, and other traumatic experiences.

Therapy can be useful in managing symptoms and addressing their underlying causes. There is an abundance of mental health providers that specialize in their own unique styles of therapy along with physicians that can provide medications to help address the symptoms. However, patients respond differently to the various methods of treatment available. What might work well for one person can have absolutely no effect on another.

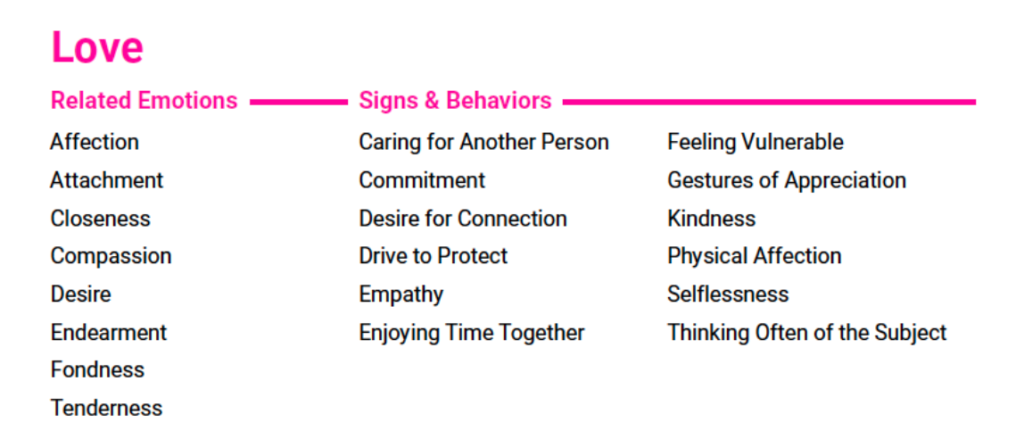

Emotional support animals (ESAs), also referred to as “assistance animals,” provide a new method for treating patients with PTSD. ESAs are not considered service animals, and there are no training or species requirements to qualify as an ESA under the Fair Housing Act. Any animal, from a professionally-trained Labrador Retriever to a hamster from the local pet store, can be categorized as an assistance animal with the correct documentation from a qualified mental health professional. Because the treatment method is relatively new, there is no landmark study that has conclusively determined the effects of having an ESA. However, there are a few common themes seen across research papers on the subject. The animals provided “emotional work” by alleviating feelings of worry and loneliness in addition to providing comfort, “practical work” by promoting physical activity and distracting from symptoms, and “emotional nourishment” by enabling social interaction (Brooks, et al., 2018). A preliminary study of an animal-assisted intervention program applied this technique to the treatment of children exposed to domestic violence, many of them exhibiting symptoms of PTSD and other clinical disorders before treatment. During the program, the participant would perform structured activities with the animal, such as playing, grooming, or feeding, in conjunction with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Even though there was no significant improvement in aggressive or unruly behavior that is associated with the externalization of symptoms, the researchers observed an overall decrease the symptoms of PTSD, as well as a decrease in the internalization of such symptoms in the form of anxiety or depression (Muela, et al., 2019). The benefit to the children’s’ emotional well-being demonstrated by this study shows the potential of assistance animals and the need for further research.

Even though most studies report that participants experience mental health benefits, it is unclear whether the type of activity done with the ESA changes the level of improvement. In order to optimize treatment plans, it is important to know what strategies would optimize the available time. The categories compared for the purposes of this experiment were playing, walking, and cuddling. This case study seeks to observe the effect of the activity performed with an ESA on the mood and low-level stress response of the participant.

Materials and Methods

I monitored my own mood and responses over the course of the case study. A therapist diagnosed me with PTSD within the past year due to my experience with domestic violence. Based on his recommendation, I was seeking treatment through talk-therapy and was prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors by a psychiatrist, which I continued to take over the course of this study. The emotional support animal used was a 50-pound cattle dog/ kelpie mix, Theo, which I adopted approximately three weeks before the study. Theo is a very calm, six-year-old dog who primarily spends his days napping on the couch or running outside. He loves physical affection and treats but does not seem to be interested in dog toys of any kind.

A baseline assessment was conducted at the beginning of each activity. The assessment consisted of a short journal entry of my thoughts and mood before and after being exposed to a photo and text conversation that typically triggers a minor emotional response due to traumatic associations; the photos were not graphic and were known to not cause an overwhelming response. At the top of the page, I recorded a rating of my mood on a scale of one to ten. The scale had no specific meanings associated with the values and was based on an intuitive response. My writing primarily focused on physical sensations, such as chest pain and changes in breathing, as well as my thoughts and what I focused on during that time.

I categorized the activities into cuddling, walking, and running/playing. The last category is combined because of the Theo’s lack of interest in dog toys and typical play activities. Instead, we would play a game similar to tag where he would chase me as I ran. The timing of each session varied due to Theo’s needs and tolerance of different activities. Once we completed the activity, I exposed myself to the same image as the beginning of the session and scrolled through an old text conversation that was consistent for each session throughout the study. I recorded my response in the same format as the initial journal entry. Different photo stimulus was used for each trial, and a series of similar images was used so that declines in responsiveness would not be attributed to overexposure.

At the end of the study, I compiled the journal entries and analyzed the results, comparing my mood ratings and the physical nature of my stress responses as well as identifying key words and phrases.

Results

My mood improved after each activity performed. On average, playing showed the highest increase in my mood ratings, averaging an increase of 1.5. Walking showed the next greatest improvement, averaging at 0.75, and cuddling closely followed with an average increase of 0.5. These numbers do not provide any specific revelations about how the characteristics of my mood changed, but they do offer a comparative scale. Both activities performed outdoors ranked higher than the activity performed indoors, possibly due to the benefits of being outside combined with the effects of my ESA. Even though cuddling seems to only offer a small increase in mood, it offered a more meditative experience where I was able to reflect upon past trauma and remain calm. The outdoor activities acted more as a distraction, not allowing me to dwell on old memories for too long before being pulled away to focus on Theo.

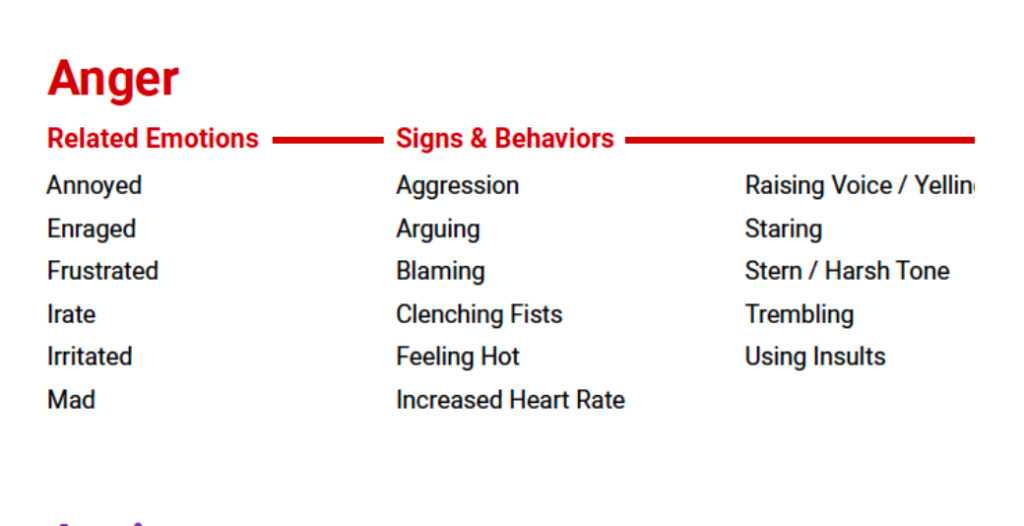

I noted feeling physical symptoms of stress before every session, but the response was less severe after cuddling. The common symptoms I noticed were changes in my breathing pattern, a pressure at the top of my chest, and an ache in my left forearm. This set of responses was known to occur before the study and was not unique to this set of stressful situations. After cuddling, I reported noticing a “hitch in my breath” when opening the messages app that quickly subsided and my breathing returned to normal. However, before that specific cuddling session, I had noted a pressure in my chest and a subsiding pressure in my arm. Before the final cuddling session, I felt pressure in my chest and arm, changes in breathing, as well as a “rising feeling of panic.” However, afterwards, the extremity of the physical response was limited to a “slight change in breathing and chest sensation,” which was a significant improvement from the previous entry. Additionally, I felt less of a physical response to typing or writing the abuser’s name after cuddling, which I typically refrain from writing unless absolutely necessary. Even when I still noticed a response to the stimuli, the physical indicators suggest that the stress was less severe after cuddling.

Walking provided a greater reduction in physical stress responses than cuddling, and there were no noticeable stress-induced sensations after playing. After one walking session, I did report a localized ache in the outer portion of my left wrist, which is similar to a common stress indicator, but it did not cover the inside part of my forearm where the related response would usually occur. This was the only recorded instance of a physical response after performing an outdoor activity with Theo. In all my other entries for walking and playing, there were combinations of the various physical sensations before the activity, but none were reported after. Similar to cuddling, there was also a decreased response to writing the abuser’s name. Since I usually use the monitored aches and abnormal sensations to determine my level of stress, the intervention of an ESA demonstrated significant improvement in the severity of my reaction to low-level triggers.

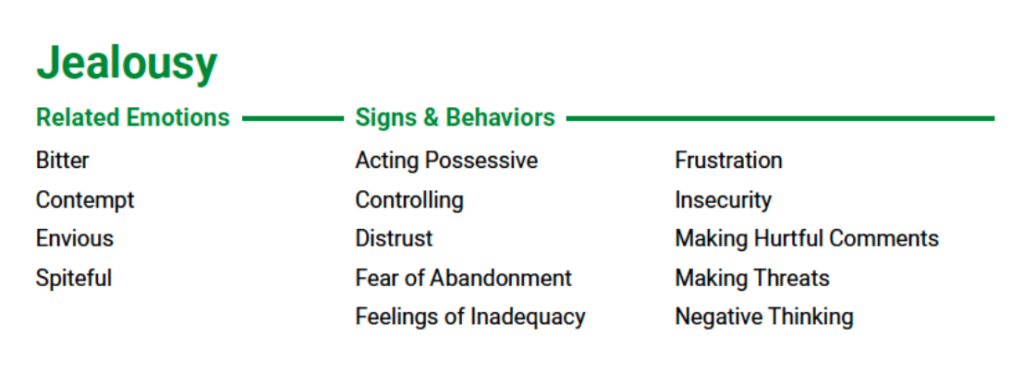

Another beneficial change that occurred across all activities was a shift in what I focused on in the stimuli. When I opened the last text conversation with the abuser before each activity, I primarily focused on his insults and vulgar profanity. My eyes were drawn to reading what was being said, and I almost felt like I was being verbally attacked all over again. In contrast, I focused more on my responses to his statements after each activity, regardless of which category the activity fell into. I was no longer feeling vulnerable; instead, I felt justified in my assertions and irritated at his attempts at manipulation. When I wrote about his messages in my journal entries after the sessions, my responses demonstrated a greater sense of annoyance or apathy compared to the stress I felt beforehand.

After the activity, regardless of which category it fell into, my journal entries showed a greater attention to the background of the pictures as well as a few less serious descriptions of the abuser’s appearance. Even though I noticed a few objects in the background when I initially looked at the photos, I was more observant and able to determine the context of the photo, such as a Halloween or dojo party. In the original entries, I would glance at the images, but paid little attention to why certain objects or people were there and mostly focused on how they juxtaposed the abuser’s face. Often, this contrast would make him appear “like a cardboard cutout” that felt like it was “staring at me” and did not fit in with the other lively subjects in the photos. While I continued to harshly comment the photos after my activities with Theo, I also wrote some comments that were a little more absurd and less stressed. In response to his yellow sweatshirt, I wrote “Banana or lemon. Rotten on the inside.” This statement made me want to continue writing a journal in a more poetic style to help vent some of my frustration and turn it into a less serious form of art. The most notably cheerful statement came after I spent time playing with Theo. I audibly laughed and wrote “he kind of looks like a worm.” This observation still brings a bit of amusement, even though I have to picture the image again. After the activities, my improved mood seemed to provide a buffer against the uncomfortable images and decrease the emotional toll of the associations.

My time spent with Theo also showed signs of mental improvement that were not directly related to mood or stress response. One trial was omitted from the mood average because of the large deviation from the regularly performed activities, but it did provide important insights to how Theo has improved my emotional well-being. During the first play session, I was approached by a photographer associated with the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) who was interested in taking photos of Theo and me. Even though I would normally be self-conscious about my appearance after quickly throwing my hair up in a messy bun and running around on the grass, I happily agreed to be photographed. This unusual occurrence significantly boosted my mood and the presence of Theo encouraged me to do something that I would have once considered to be far outside of my comfort zone.

Discussion and Conclusions

Playing with my ESA provided the greatest improvement in mood and the fewest physical signs of stress response after the activity. These results suggest that more active interactions with an ESA would provide the greatest benefits to an individual. However, since play activities were performed outside, it is important to expand future studies to analyze how the environment impacted the results by testing the activity in different location. Either way, this method provides a therapeutic benefit that an individual can achieve with their ESA.

There are also some notable benefits to cuddling with an ESA, despite the activity showing the least significant improvement in mood. While walking and playing provided a distraction from intrusive thoughts and stressors, cuddling allowed my mind to wander and think about traumatic memories without the typical feeling of being overwhelmed. In this case, it may be useful to combine the act of touching or cuddling an emotional support animal with some form of talk-based therapy with a licensed mental health professional. In this controlled setting, it may help the patient address the underlying issues without becoming overwhelmed by an emotional response that would normally come from having a conversation about one’s traumatic experiences. This potential benefit might not be as effective when performing more active activities where the individual is more distracted than meditative.

Because I tested myself, the results may have been influenced by what I expected to happen or what I observed after first few sessions. For this reason, it is important to have a larger group of subjects and to perform a double-blind experiment, where the experimenters are unaware of which journal entry they are analyzing, and the subjects do not know what the expected results are. Some other potential factors that influenced the results were the different environments and levels of social interaction. Even though the walk and playing took place in the same outdoor space, the cuddling sessions were performed inside, which may have influenced the results. The different amounts of social interaction that occurred when outside may have also affected the results, which would have been amplified by the effects of quarantine. In order to improve upon this case study, these external factors should be accounted for and standardized.

Further research is needed to understand the effects of different species of ESAs and the personalities of the assistance animal and its owner. Since this study only included one animal, it is unclear whether the benefits would be consistent across different species. Would the hamster from the pet store provide the same benefits as thee professionally-trained Labrador Retriever? It is also important to test how the personality of the animal and how it corresponds with the owner’s personality and preferences since animals differ greatly in their levels of playfulness and affection. While I am highly fond of animals, especially dogs, this is not the case for all people. The compatibility of the animal and the owner could potentially impact the therapeutic benefits.

References

Brooks, H. L., Rushton, K., Lovell, K., Bee, P., Walker, L., Grant, L., & Rogers, A. (2018). The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1613-2

Crocq, M. A., & Crocq, L. (2000). From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder: a history of psychotraumatology. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 2(1), 47–55.

Muela, A., Azpiroz, J., Calzada, N., Soroa, G., & Aritzeta, A. (2019). Leaving A Mark, An Animal-Assisted Intervention Programme for Children Who Have Been Exposed to Gender-Based Violence: A Pilot Study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(21), 4084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214084

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml